Description: Alexei Navalny in 2006. A few years later he described Russia’s ruling party, United Russia, as a “party of crooks and thieves.”

(Staff) Russia’s most famous opposition leader and political prisoner died suddenly on Feb. 16 while incarcerated in the Arctic gulag. Alexei Navalny was only 47. The Kremlin denies any involvement in his death.

The Yale-educated lawyer ran for office to advocate reforms against corruption in Russia and against President Vladimir Putin and his government. Navalny founded the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) and was recongized by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience. He was awarded the Sakharov Prize for his work on human rights.

Alexei Navalny was born June 4, 1976 of Russian and Ukrainian descent. He grew up in Obninsk, about 100 km southwest of Moscow, but spent his childhood summers with his grandmother in Ukraine, acquiring proficiency in the Ukrainian language.

Navalny was originally an atheist, but later became a member of the Russian Orthodox Church. He said that turning to the Orthodox Church made him feel a “part of something large and universal.”

Through his social media channels, Navalny and his team published material about corruption in Russia, and organized political demonstrations. In a 2011 radio interview, he described Russia’s ruling party, United Russia, as a “party of crooks and thieves,” which became a popular epithet. Navalny and the FBK published investigations detailing alleged corruption by high-ranking Russian officials and their associates.

Navalny twice received a suspended sentence for embezzlement, in 2013 and 2014 – both criminal cases were widely considered politically motivated and intended to bar him from running in future elections. He ran in the 2013 Moscow mayoral election and came in second with 27% of the vote but was barred from running in the 2018 presidential election.

Four years ago, in August 2020, Navalny was hospitalised in the Siberian city of Omsk. His supporters had him airlifted to Berlin where doctors concluded that he had been poisoned with the nerve agent Novichok. He was discharged a month later. Navalny accused Putin of being responsible for his poisoning, and an investigation implicated agents from the Federal Security Service.

In January 2021, Navalny voluntarily returned to Russia and was immediately detained on accusations of violating parole conditions while he was hospitalised in Germany. Following his arrest, mass protests were held across Russia. In February 2021, his suspended sentence was replaced with a prison sentence of over 2 1⁄2 years’ detention, and his organisations were later designated as extremist and liquidated.

In March 2022, Navalny was sentenced to an additional nine years in prison after being found guilty of embezzlement and contempt of court in a new trial described as a sham by Amnesty International; his appeal was rejected and in June, he was transferred to a high-security prison. In August 2023, Navalny was sentenced to an additional 19 years in prison on charges of extremism.

In December 2023, Navalny went missing from prison for almost three weeks, then re-emerged in an Arctic Circle corrective colony. There on Feb. 15 he was seen joking and laughing during a court appearance where he appeared fit and healthy – yet he died mysteriously the next day. His death sparked protests, both in Russia and around the world.

“The truth set Navalny’s soul free,” wrote Raymond J. de Souza in the Feb. 24th issue of the National Post. “Whether Putin specifically ordered his murder or he died of the harsh conditions matters little. He is a martyr of the Putin regime, which in any case attempted to kill him earlier with a chemical nerve agent….For the Christian believer, that the truth shall set you free is ultimately an eschatological claim. In this world witness to the truth is often offered from the grave, as the white-robed army of martyrs attest.”

De Souza noted that Navalny knew he’d be arrested again if he returned to Russia yet he did so to offer his witness. And ‘martyr’ means ‘witness.’

At the conclusion of his show trial the Christian activist spoke of his faith directly to the presiding judge:

“Your Honour, do you want me to talk to you about God and salvation?” Navalny asked. “The fact is that I am a religious person … I was quite a militant (atheist) myself. But now I am a believer, and it helps me a lot in my work.

“And it is said, ‘Blessed are those who thirst and hunger for righteousness, for they shall be filled,’” Navalny continued. “I’ve always perceived this particular commandment as more or less an instruction for activity. And so, certainly not very much enjoying the place where I am, nevertheless, I don’t have any regrets about being back, about what I’m doing … I did not betray the commandment.”

De Souza wrote: “In the end, it was Navalny, not his jailers, who was free. In the end, it was Navalny whose soul was filled even as his body was cold and fatigued and broken and hungry.

“The killing of Alexei Navalny does not tell us anything new about the Russian regime. Yet it does remind us of something important about the Russian soul, the soul of a land that has produced millions of martyrs. Navalny belongs to that tradition, which includes the witness of believers and non-believers alike, from [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn to [Andrei] Sakharov.”

Navalny had already shared a message for his fellow Russians in the event of his death. In the documentary Navalny (2021), directed by Canadian Daniel Rohr, Navalny declared:

“Listen, I’ve got something very obvious to tell you. You’re not allowed to give up. If they decide to kill me, it means that we are incredibly strong. We need to utilize this power, to not give up, to remember that we are a huge power, that is being repressed by these bad dudes. We don’t realize how strong we actually are. The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good people to do nothing. So don’t be inactive.”

And then he smiled.

His sudden death comes less than a month before a sham election that is all but certain to give Putin another six years in power. The former KGB agent came to power a quarter century ago in 1999.

Navalny’s mother was shown a medical certificate stating that her son died of “natural causes.” Lyudmila Navalnaya said authorities tried to force her to agree to a secret burial but she refused.

Since her son’s death, 400 people have been arrested across Russia as they tried to pay tribute to him with flowers and candles. Police would remove the flowers at night, but more kept appearing.

Besides his mother, Navalny is survived by his wife Yulia Navalnaya and two children, a daughter Darya, who is studying at Stanford University, and a son Zakhar.

“Putin killed my husband,” his widow told the European lawmakers in Strasbourg on Feb. 28. “On his orders, Alexei was tortured for three years. He was starved in a tiny stone cell, cut off from the outside world and denied visits, phone calls and then even letters,” she said. She has vowed to continue her husband’s work but in exile.

Two days after her husband’s death Navalnaya spoke at the European Union’s Foreign Affairs Council. She called on Western leaders not to recognize the results of March’s presidential election, to sanction more people in Putin’s circle and to do more to help Russians who have fled abroad.

“By killing Alexei, Putin killed half of my heart and half of my soul,” she said. “But I still have the other half, and it tells me that I have no right to give up.”

Navalny’s funeral was held on March 4 in the Church of the Icon of the Mother of God in the Moscow district of Maryino where Navalny used to live. Plans for a separate civil memorial service in a hall that could accommodate more people were blocked by the Kremlin but thousands marched to the cemetery where he was buried. TAP

EASTER is the most important festival for Christians, because it is the basis of our faith.

continue reading

ON NOV. 20, 2023, Bp. Andrew Asbil issued an “important liturgical note” to the Diocese of Toronto. His choice of date was intentional: he noted that it is was the “Trans Day of Remembrance and Resilience.” He quoted from Genesis 1, and spoke of God’s creation – “an act of love,” which “includes a vast spectrum of diversity, including human diversity.

continue reading

IN THE GOSPEL LESSON for this first Sunday in Lent, we have Saint Matthew’s account of the temptations of Jesus. This lesson is clearly intended to establish in our minds the meaning and the message of the Lenten season, and we should examine it with careful attention. And perhaps before we do that, it would be useful to think for a moment about the background and context of the story.

continue reading(Staff) Russia’s most famous opposition leader and political prisoner died suddenly on Feb. 16 while incarcerated in the Arctic gulag. Alexei Navalny was only 47. The Kremlin denies any involvement in his death.

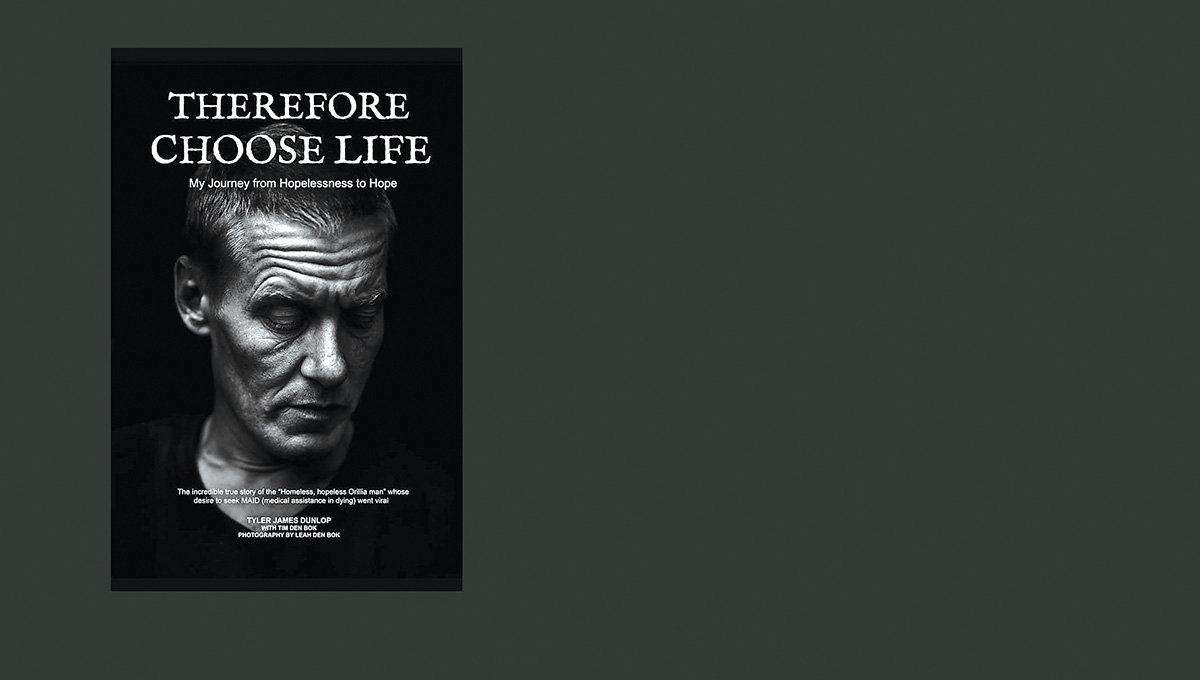

By Tyler James Dunlop with Tim den Bok

Independently published, 2023

Review and Comment by Margaret Cottle, MD

AT THE annual Mere Anglicanism conference, you’re likely to hear speakers from Oxford, Cambridge and McGill quote Goethe, Nietzsche and Rousseau. But what you come away remembering best are tales of some of the ordinary folk who influenced these scholars’ lives

JUST OVER thirty years ago two young women, Teresa from rural New Brunswick, Jane from rural Nova Scotia, were “sent” to a week-long camp for youth. That reluctant start has grown into a life-long friendship. Even with almost 3000 km now between them, they still consider each other close and supportive friends. Jane Neish, a teacher in Rankin Inlet, and Teresa d’Entremont, a victim services officer in Yarmouth, N.S., both say they owe a lot of what they hold in common to the influence of St. Michael’s Youth Conference (SMYC).

Copyright © 2024 The Anglican Planet. All rights reserved